Just a single dose of calcitriol—the active form of vitamin D—reversed paralysis in mice with an experimental form of multiple sclerosis, a new study finds. Once established, the relapse could be maintained through dietary supplementation with the vitamin.

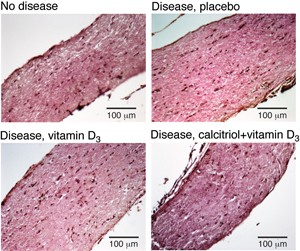

One calcitriol dose plus supplementary vitamin D3 reversed the disease-induced swelling of the optic nerve. © C. E. Hayes, U. Wisconsin

The findings, reported online August 6, 2013, in the

Journal of Neuroimmunology, show that a dose of calcitriol triggers a brief changing of the guard in the central nervous system (CNS): Numbers of inflammation-dousing regulatory T cells ramp up, while those of their troublemaking cousins, the Th1 and Th17 cells, dip (

Nashold et al.,2013). The therapeutic effects live on in mice kept on a vitamin D-fortified diet.

The investigators, led by Colleen Hayes, Ph.D., a professor of biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, hypothesize that treatment with the active hormone triggers the death of autoreactive T cells in the CNS. Continued supplementation with cholecalciferol (vitamin D3), the researchers propose, may prevent new self-reactive T cells from getting any crazy ideas.

“It’s well established that vitamin D deficiency is associated with the onset of MS and frequency of relapses,” said Michael Demetriou, M.D., Ph.D., director of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society Designated Comprehensive Care Clinic at the University of California, Irvine, in an interview with MSDF. Demetriou, who studies the role of T cells in MS, was not involved in the study. “But this paper actually shows that calcitriol may be used to treat relapses [in mice] rather than just preventing them.”

Vitamin D and MS

Multiple sclerosis has been linked to lack of sun exposure since 1960, when researchers noticed that rates of the disease were highest in populations living far from the equator (Acheson et al., 1960). After researchers discovered in the 1970s that ultraviolet rays catalyze the reaction that produces the precursor to calcitriol, sporadic studies drew connections between MS and the hormone. Coordinated research in the area truly began following a 1997 proposal by Hayes and colleagues that vitamin D3 played a role in regulating the immune system in MS.

Since then, studies have shown that people with lower levels of vitamin D have a higher risk of MS. But this correlation says nothing about causation—it’s possible that low vitamin D levels cause MS, but also that people with MS avoid sunlight, resulting in low vitamin D levels. However, one study demonstrated that low levels of vitamin D before age 20 was associated with an increased risk of MS diagnosis 10 years later (Munger et al., 2006), strengthening the argument for vitamin D’s causative role. Nevertheless, whether vitamin D supplementation could have the power to stop or reverse MS continues to be an area of intense research.

While vitamin D is best known for its role in bone maintenance, it has also been shown to play a role in vascular health, neurological function, and tempering the immune response. But the vitamin doesn’t function “as-is.” Rather, sunlight catalyzes the reaction that creates cholecalciferol in the skin. This precursor gets transformed into another form, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, in the liver. The kidneys, the skin, the CNS, and some immune cells take care of the last step, producing the active form of the hormone, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, also known as calcitriol. This hormone then binds to intracellular vitamin D receptors, which jump onto DNA to turn genes on and off.

Hayes’s newly published study represents more than a decade of work. Between 2000 and 2004, Hayes and colleagues tested their hypotheses about calcitriol in mice withexperimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a disease that shares some similarities with multiple sclerosis in humans. After researchers induce the disease by injecting mice with a peptide fragment derived from myelin basic protein along with an adjuvant, the mice rapidly show paralysis that moves from the hind legs up to the fore legs.

The investigators showed that a single dose of calcitriol induced a transient remission in mice with established EAE, and daily or weekly doses of the hormone induced a permanent remission. But soon after this discovery, a small study in humans linked regular calcitriol use with an unacceptable risk of hypercalcemia (Wingerchuck et al., 2005). So Hayes decided to test whether vitamin D3 supplementation, which does not pose a significant hypercalcemia risk, would be sufficient to treat the disease. Unfortunately, treatment with vitamin D3 alone did not promote remission in mice with established EAE.

Calcitriol and T cells

The team then looked to the T cells to get a better handle on the mechanism of calcitriol-induced remission. The investigators found that calcitriol rendered autoreactive T cells more sensitive to external death signals, and in a recent study, they showed that vitamin D receptor expression on CD4+ T cells was necessary for calcitriol to prevent disease in mice with EAE (Mayne et al., 2011).

In the currently published work, the researchers show that the balance of T cells in the CNS shifts one day following calcitriol treatment. Total numbers of CD4+ T cells in the CNS dropped by nearly 60%, with IFN-?-producing and IL-17-producing CD4+ T cells—those thought to be involved in destructive responses—accounting for much of that loss. On the other hand, the number of CD4+ T cells expressing Helios and FoxP3, also known as regulatory T cells or Tregs, nearly doubled. One week later, the number of CD4+ T cells in the CNS remained low, and even regulatory T cells dropped by more than half of their pretreatment numbers.

The rapid changes in T cells induced by calcitriol motivated the researchers to test whether just a single dose of the hormone followed by supplementation with vitamin D3might induce remission and stave off relapse. The results show that a single dose of calcitriol led to a 9-day remission in 92% of the mice. When mice were put on a diet supplemented with vitamin D3 following a single dose of calcitriol, the once-paralyzed mice remained fully ambulatory for the remainder of the experiment.

“As long as we could afford to keep them, the animals stayed in remission,” Hayes said. “They still dragged their tail a little bit, but in the grand scheme of things that’s a success, because this disease in mice is very aggressive compared to the disease in humans.”

Hayes proposes that calcitriol triggers the death of autoreactive T cells, and vitamin D3prevents new cells from flaring up. Her hypothesis is consistent with recent work from Demetriou’s lab (Mkhikian et al., 2011), which showed that calcitriol triggers the upregulation of a glycosylation-mediated cell-death pathway in T cells. “Calcitriol likely has multiple effects, but our previous results suggest that one of those effects is the upregulation of glycosylation,” Demetriou said. “These results [from Hayes’s study] completely fit with what we would expect in that situation.”

Although the final step in calcitriol synthesis is thought to occur in the kidneys, Hayes suspects that cells in the CNS also contribute to production of the active hormone. In people with MS, Hayes speculates, this pathway could be blocked. A single dose of calcitriol, Hayes said, could be like pressing the reset button.

The study adds to a solid body of literature implicating vitamin D in the suppression of MS symptoms via T cells, said Lawrence Steinman, M.D., a professor of neurology and neurological sciences, pediatrics, and genetics at Stanford University, who was not involved in the study. Indeed, recent work from Steinman’s lab showed that calcitriol blocks the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17 in human and mouse T cells (Joshi et al., 2011). “Now we need to know definitively whether it works in humans,” Steinman said in an interview with MSDF. “And that’s the challenge.”

Key open questions

- How does calcitriol exert its effects on autoreactive T cells in EAE?

- Are regulatory T cells required for the therapeutic effects of calcitriol in EAE?

- Will a single dose of calcitriol followed by vitamin D3 supplementation treat MS in humans?

Disclosures

The study was supported by grants from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and the Robert Draper Technology Innovation Fund. Drs. Hayes, Steinman, and Demetriou reported having no relevant financial disclosures.